英文首页﹀

Long-Term Finance Provision: National Development Banks vs. Commercial Banks

2022-06-07

Long-Term Finance Provision: National Development Banks vs. Commercial Banks

Bo Hu, Alfredo Schclarek, Jiajun Xu*, Jianye Yan

The present op-ed is based on the following academic publication:

Hu, Bo, Alfredo Schclarek, Jiajun Xu, and Jianye Yan, Long-term finance provision: National development banks vs commercial banks, World Development, 158 (2022) 105973.

* Corresponding author: Jiajun Xu

Affiliation: Institute of New Structural Economics, National School of Development, Peking University

Address: Langrun Garden 165, Yiheyuan Road No. 5, Peking University, Beijing, P.R. China, 100871

E-mail: jiajunxu@nsd.pku.edu.cn;

I. Long-term finance: Why does it matter? Why is it in short supply?

Long-term finance plays a significant role in promoting long-term economic growth and financial stability. However, long-term finance is often in short supply in a laissez-faire decentralized banking system with commercial banks only. Commercial banks are often reluctant to provide long-term finance because they take household deposits as their main funding source and hence suffer from maturity mismatch, liquidity risks, and potential runs. Furthermore, coordination failures among profit-driven commercial banks result in a “maturity rat race,” in which all lenders shorten the maturity of contracts to protect their claims. Such a deficit in the provision of long-term finance is particularly severe in developing countries because credit rationing is further exacerbated by underdeveloped financial systems, poor legal and institutional frameworks, and unstable political and macroeconomic environments.

In the wake of the recent global financial crisis that erupted in 2008, reversing the prolonged decline in the supply of long-term funding tops the agenda of policy makers worldwide. G20 leaders have highlighted the importance of long-term financing in boosting infrastructure investment to foster long-term growth. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development has developed the “High-Level Principles on Long-Term Investment Financing by Institutional Investors” report, which G20 finance ministers and central bank governors have endorsed.

II. Build the first global database to test whether NDBs lend longer than commercial banks

One key way for governments to overcome the scarcity of long-term finance is to establish national development banks (NDBs) with the official mission of providing long-term capital to fill the market gaps. Schclarek et al. (2019) provide the first theoretical model for explaining why NDBs may lend longer than commercial banks. But little systematic research has been conducted to examine whether NDBs have provided that much-needed long-term finance. Anecdotal evidence has suggested mixed findings.

On the one hand, some renowned NDBs seem to have provided long-term capital as expected. For example, the German NDB Kreditanstalt fur Wiederaufbau (KfW) was created in 1948 to finance the long-term reconstruction of Germany after World War II. In 2020, KfW’s total assets were 546 billion euro (equivalent to 668 billion USD), accounting for 17% of the German GDP. The ratio of long-term loans to short-term loans is about 5:1. Another example is the China Development Bank (CDB), which was established in 1994. CDB had total assets of more than 2.62 trillion USD in 2020, on par with the largest U.S. bank, JP Morgan, and accounting for nearly one-fifth of Chinese GDP. CDB has provided long-term loans to finance basic infrastructure and pillar industries in China and has become a key provider of long-term infrastructure financing in developing countries since 2005.

On the other hand, the World Bank’s Global Financial Development Report (2015) has noted that political capture and poor corporate governance practices undermine the success of NDBs in the provision of long-term finance. The World Bank further argues that good corporate governance of development banks is difficult to establish in weak country-level institutional environments. Hence, the World Bank maintains that governments should refrain from making direct efforts to build NDBs to fill the financing gaps in the provision of long-term finance. Instead, the World Bank recommends that governments need to focus on fundamental institutional reforms, including putting in place sound legal and contractual environments.

To fill the gap, we are the first to build the first global database on development financing institutions worldwide systematically examine whether NDBs on average lend longer than commercial banks. We distinguish NDBs from commercial banks by rigorously identifying NDBs worldwide. To build a credible list of NDBs, we must establish what NDBs are; we do so by proposing qualification criteria that distinguish NDBs from similar institutional arrangements. We then systematically apply these criteria to each member of DFIs and DFI-like associations as well as every institution in the DFI-like category, such as specialized financial institutions in the official classification of national financial systems country by country. This comprehensive list of NDBs enables us to systematically compare the loan maturity of NDBs with that of commercial banks worldwide.

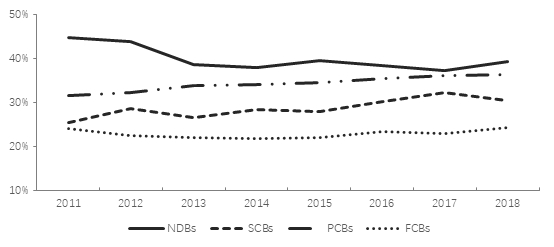

In our paper, we econometrically examine whether the proportion of long-term loans in the total loan portfolio of NDBs is on average larger than that in commercial banks. Matching our list of NDBs with bank-level data from BankFocus, we can build a large international data set for 1,253 banks, of which 58 are NDBs, 112 are state-owned commercial banks (SCBs), 695 are privately owned domestic commercial banks (PCBs), and 388 are foreign commercial banks (FCBs) from 106 countries during the 2011–2018 period. We find NDBs lend longer than commercial banks in general and privately owned commercial banks in particular. Figure 1 shows that NDBs on average lend much longer than commercial banks. For instance, about 48% of NDB loans are long-term, which is much higher than commercial banks. After controlling for country- and bank-level factors, this result is statistically significant.

Figure 1. Average Ratio of Loans to Customers With a Maturity of More Than 5 Years in Total Outstanding Loans by NDBs, SCBs, PCBs, and FCBs

Data Sources: The Global Database on DFIs and PDBs by the Institute of New Structural Economics at Peking University and French Development Agency at http://www.dfidatabase.pku.edu.cn/; BankFocus.

III. What enables NDBs to provide the long-term finance?

As a unique bank type, NDBs are specialized financial institutions initiated and steered by central governments to fill the financing gap. Compared with commercial banks, NDBs possess the following distinctive features that may enable them to provide long-term loans.

Development-oriented mandates

Unlike profit-maximizing commercial banks, NDBs are mandated to proactively pursue public policy objectives. Because NDBs may be more willing to internalize certain positive externalities of longer-term loans to firms and take on risks that private commercial banks do not, they are willing to lend longer-term than private commercial banks, even if doing so entails higher risks.

Long-term liabilities

Long-term funding on the liability side enables NDBs to provide long-term loans on the asset side. Because commercial banks rely predominantly on short-term bank deposits that may be withdrawn at any moment, commercial banks are prone to higher maturity mismatch and refinancing risks when providing longer-term loans. By contrast, NDBs usually do not take short-term household deposits as commercial banks do, or they may be forbidden from doing so. For example, KfW and Development Bank of Mongolia are prohibited from taking household deposits in their articles of agreement. Based on firsthand data of worldwide NDBs’ funding sources, the third New Structural Economics Development Financing Report discovers that NDBs often rely on government creditworthiness to issue long-term bonds in capital markets at a relatively low cost or rely on on-lending from multilateral development banks. Moreover, compared with commercial banks, NDBs rely more on recapitalizations and internal financing to finance their lending. Therefore, NDBs can grant longer-term credits without incurring substantial maturity mismatch and refinancing risks.

Higher collateral value of bond issuances by NDBs

In case of the liquidity risk, if the bonds issued by NDBs to finance their bank lending have higher collateral value (i.e., the maximum amount that banks may obtain by issuing bonds) than those issued by commercial banks, then NDBs may lend longer-term to firms than commercial banks do. NDBs may enjoy a greater collateral value of their bonds than private commercial banks because the state (the owner of the NDBs) provides higher willingness and capacity of recapitalization than private bank owners in case of difficulties when honoring the issued bank bonds. Furthermore, NDBs may even have an advantage over state-owned commercial banks in providing long-term finance if NDB bonds enjoy higher market liquidity than state-owned commercial banks owing to the larger size of their bond issuances, thus enhancing their collateral value.

The acquisition and dissemination of industrial expertise

NDBs can foster the acquisition and dissemination of expertise in providing long-term loans to finance new industries. In a laissez-faire decentralized banking system, commercial banks often underinvest in and undertransmit expertise in long-term industrial finance. Long-term projects involve large sunk costs, which require cofinancing by several banks. However, cofinancing induces a free rider problem in monitoring effort. Each bank will provide a limited monitoring effort because part of the marginal return from this effort will accrue to other banks. Consequently, insufficient monitoring jeopardizes project profitability, thus discouraging the cofinancing of long-term projects by commercial banks.

IV. How to unleash the potential of NDBs to provide the long-term finance?

The world is witnessing a renaissance of NDBs initiated by central governments to advance development goals. Both advanced and developing countries alike, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, India, Nigeria, and Ghana, have recently established or are planning to build new NDBs to provide long-term finance to meet economic, social, and environmental development challenges. To unleash the potential of NDBs for providing the long-term finance, we have drawn the following policy implications:

First, policy makers should not dismiss the role of NDBs in providing long-term finance simply based on anecdotal evidence. Although it is true that not all NDBs have been successful and some NDBs have failed miserably in the past, this does not mean that NDBs cannot play a maturity-lengthening role. There are sound theoretical rationales behind the belief that NDBs are well positioned to provide long-term finance to fill the financing gap. Relying on a comprehensive panel data set of NDBs worldwide, our empirical analysis demonstrates that NDBs on average lend longer than commercial banks. Given the fact that NDBs are prevalent worldwide, we should shift the policy debate from whether governments should establish NDBs to how to make NDBs work better.

Second, NDBs should be well capitalized to unleash their potential for scaling up the provision of long-term finance. This policy recommendation is particularly relevant given the trend that NDBs are undergoing a renaissance worldwide. Even if NDBs have comparative advantages in providing long-term finance, their contribution to filling the financing gap would be substantially undercut if they are undercapitalized. Hence, the maturity-lengthening role of NDBs is more relevant for countries that have governments with stronger credibility, finances, and net worth than for countries with governments plagued by credibility concerns, over-indebtedness, and excessive fiscal deficits. For countries whose governments are in a relatively weak financial position, their NDBs should try to seek on-lending from multilateral development banks or NDBs from countries with a strong financial foothold.

Third, NDBs need to focus on long-term finance to fill the financing gap and avoid unfair competition with commercial banks. NDBs are initiated and steered by governments to fulfill public policy objectives; accordingly, NDBs often enjoy government support, such as sovereign guarantee, preferential tax treatment, and concessional borrowing. NDBs should not provide short-term loans to firms that could have access to credits from commercial banks. Otherwise, NDBs would create distortions in credit markets and crowd out commercial banks. Recently, there has been a worrying trend that a few NDBs decide to take household deposits because they lack alternative funding sources. Because taking household deposits may create the maturity mismatch problem, it would undercut the comparative advantage of NDBs in providing long-term finance.

Fourth, governments should not only provide sovereign guarantee to enable NDBs to issue long-term bonds on capital markets to enable them to provide long-term loans but should also foster and improve the development of bond markets. If the liability structure of NDBs is deficient in long-term funding sources, NDBs would fall short of providing the much-needed long-term finance on their asset side. Based on the experience of CDB in China, CDB as a “bond bank” has helped incubate China’s bond markets owing to government support. Upon its establishment in the early 1990s, China’s bond markets were almost nonexistent. To ensure that CDB had sufficient funding sources, the People’s Bank of China placed the administrative order upon state-owned commercial banks to purchase CDB bonds, which helped turn short-term and small-scale household deposits into long-term and large-scale funding for CDB. Later in 1998, with the strong support of the Chinese government, CDB started to pilot bond issuances via market means. Since then, CDB has been a primary bond issuer and innovated new bond products on the China’s interbank bond market. The frequency of CDB bond issuances is much higher than government bonds, so the coupon rates of CDB bonds have acted as the anchor rate to incubate China’s bond markets. We are not arguing that the CDB case can be replicated elsewhere. But it does show that government support is essential for NDBs to mobilize sufficient long-term funding to fulfill their mandate of long-term finance provision.

Finally, NDBs need to be well governed to unleash their potential for providing long-term finance. State ownership is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, governments have to play a steering role in setting the corporate strategy of NDBs to ensure they proactively fulfill public policy objectives. NDBs cannot be deprived of essential government support to fulfill their development-oriented missions. On the other hand, governments should not unduly intervene into the microlevel loan approval or appraisal procedure of NDBs. Otherwise, undue government intervention would undermine the quality of assets, hence undercutting their ability of providing long-term finance. Therefore, governments should try to build the firewalls to guard NDBs against undue political influence and should ensure that NDBs enjoy a sufficient degree of professional autonomy to better implement their development-oriented mandates.

Looking ahead, we plan to collect firsthand data and conduct case studies to examine the variation, if any, in the provision of long-term finance among NDBs and explore under what conditions NDBs can provide long-term loans This will help us make specific policy recommendations on how to enhance the maturity-lengthening role of NDBs in the future