Research﹀

-

Latest Activities NSE International Conference NSE Symposium/Winter Camp

-

Objectives and Actions Working Groups Database Reports & Publications Governance and Partners Events Policy Briefing

No.2 | Development Strategy, Resource Misallocation and Economic Performance

2016-08-03

Content introduction:

Development Strategy, Resource Misallocation and Economic Performance

Binkai Chen

Professor

School of Economics

Central University of Finance and Economics

Cell: 86-13811709064;

&

Justin Yifu Lin

Professor

National School of Development

Abstract: This paper provides a consistent explanation to China's distinct economic performance before and after its economic reform from the perspective of government development strategy and resource misallocation. We argue that government development strategy and resource misallocation are key determinants of China's economic development. The descriptive statistics show that China's capital-output ratio is negatively correlated with per capita output, which contradicts with the predictions of standard neo-classic growth theories. We incorporate government heavy industry oriented development strategy into a two-sector model to rationalize the puzzling facts in China. The theoretic model reveals that a higher degree of heavy industry oriented development strategy will result in higher capital-output ratio and lower per capita output, which is consistent with China's stylized facts.

Based on different predictions derived from development strategy hypothesis and standard growth models, we test our hypothesis against other theories using China's prefecture level data. We find that capital-output ratio is significantly and negatively correlated with per capita output, which is consistent with the development strategy hypothesis but contradicts with the neo-classic growth theory. Further empirical evidences show that capital-output ratio rooted in heavy industry oriented development strategy is highly negatively correlated with per capita output, while capital-output ratio generated under market economy is positively correlated with per capita output. Those empirical findings suggest that government development strategy has led to high capital-output ratio and poor economic performance through resource misallocation.

Based on Chinese firm level data, we investigate the effects of development strategy on misallocation and TFP directly. We find that higher capital-output ratio is associated with higher degree of misallocation, and the positive correlation is driven by government development strategy. Heavy industry oriented development strategy will result in higher degree of misallocation and lower TFP. SOEs, non-exporters, large-sized firms and firms with bank loans are more likely to be affected by government development strategy, because those firms are the most important channels for the government to implement its development strategy.

This paper also sheds light on the development process of other less developed countries. As most less developed countries choose heavy industry oriented development strategy after World War II, development strategy and misallocation should be very important in understanding cross country income disparity.

Keywords: Development Strategy, Misallocation, Economic Development

JEL codes: D23, O1

I. Introduction

In the past three decades, China has achieved remarkable economic progress, with its real per capita GDP growing over 9% annually and people's living standards improving significantly[1]. China's achievement since 1978 can be called a miracle in economic history. However, it also poses a great challenge to the existing literature because China's experience can hardly be explained by the standard growth theories.

The neo-classic growth theory highlights the importance of saving rate and capital accumulation in determining economic performance (Solow, 1956; Mankiw, Romer and Weil, 1992). However, as an index for saving rate, China's capital-output ratio is negatively correlated with per capita output across different regions, which contradicts with the prediction of neo-classic growth theory[2]. The endogenous growth theory emphasizes the role of learning by doing, human capital, research and development (R&D) in shaping technology progress and economic growth (Romer, 1986, 1990; Lucas,1988; Grossman and Helpman,1991; Aghion and Howitt,1992). Nevertheless, those endogenous growth models cannot explain China's distinct economic performance before and after its economic reform in 1978. Meanwhile, all the factors mentioned above are just the proximate causes of the income differences, as the accumulation of physical and human capital and technology progress are themselves endogenous (Acemoglu et al., 2007; Rodrik, 2003). It is necessary, therefore, to look for other fundamental factors that underpin the proximate causes of economic development.

The existing literature identifies several possible fundamental causes of economic development, such as geography (Sachs and Warner, 1997, 2001 et.al), culture (Weber, 1930; Chanda and Putterman, 2007 et.al), luck (Murphy, et al., 1989, et.al) and institutions (Acemoglu et al., 2001, 2002, 2005; Rodrik, 2003 et.al). However, the geography, culture and luck hypothesis cannot explain China's distinct economic performance before and after 1978 simultaneously. Meanwhile, although China's economic performance is outstanding, its institutions are not so good at almost every aspect[3], which is also not consistent with the institution hypothesis.

This paper proposes an alternative explanation for the root cause of China's economic growth, which will also shed light on the process of economic development in other Less Developed Countries (LDCs henceforth). Our hypothesis is that government development strategy is the key determinants China's distinct economic performance before and after 1978. The Chinese governments pursued a heavy industry oriented development strategy before 1978, which promoted capital intensive heavy industries as the priorities of its development plan. However, heavy industry is not consistent with the comparative advantage of China at that time, as labor is abundant and capital is relatively scarce. Therefore, the government introduced a series of distortions in its international trade, financial sector, labor market, and so on in order to support the heavy industries (Lin, 2003). China has established its capital-intensive industries through various distortions. However, the economy becomes very inefficient due to misallocation of resources, which is the main reason of China's poor economic performance before 1978. The government gradually abandoned its heavy industry oriented development strategy after 1978, and switched to a development strategy that focuses on promoting the development of labor intensive industries. As labor intensive sector is consistent with the comparative advantage of China, the firms are profitable in an open, competitive market, and resources are reallocated to this more efficient sector gradually. This comparative advantage following (CAF) development strategy is the key driven force for China's rapid economic growth after 1978.

We test our hypothesis from various aspects in this paper. Firstly, based on different theoretic predictions derived from development strategy hypothesis and standard growth models, we test our hypothesis against other classic growth theories under the background of China's economic development. Secondly, we study the relationship between development strategy, misallocation and economic performance both directly and indirectly using China's prefecture level data. Thirdly, we investigate the effects of development strategy on firm productivity and resource misallocation using China's firm level dataset. Finally, we explore the channel how development strategy affects firm productivity and economic performance, and test whether it is consistent with our hypothesis.

The rest of the paper is arranged as the follows. In next section, we outline a short review of economic growth theory, and provide a puzzling fact in China which can hardly be explained by existing theories. In Section III, we construct a theoretic model to rationalize the puzzling fact in China, and derive some testable predictions from our theoretic model. Based on China's prefecture level data, section IV tests our hypothesis against the classic growth theories, and studies the role of development strategy in economic development. Section V further investigates the effects of development strategy on resource misallocation and firm productivity using China's firm level data. Section VI concludes with a discussion about the implications of our hypothesis.

II. Economic Growth Theory and the Puzzling Facts in China

According to the seminal work by Robert Solow (1956), saving rates are the key determinants of the steady-state per capita output. Numerous empirical evidences support the basic prediction of the Solow Model that saving rate is not only positively correlated with per capita output (Mankiw, Romer and Weil, 1992; Hall and Jones, 1999), but also positively correlated with economic growth rate (Barro,1991; Levine and Renelt, 1992; Islam,1995; Sala-i-Martin,1997). The role of saving rate in economic development can be easily demonstrated using standard neoclassic production function ![]() , which can also be expressed as,

, which can also be expressed as,

![]() (1)

(1)

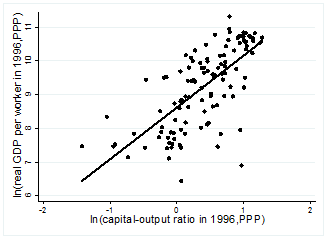

Where (Y/L) is per capita output, A is Total Factor Productivity (TFP henceforth), (K/Y) is capital-output ratio. As pointed out by Mankiw, Romer and Weil (1992), this expression is consistent with the steady state of a neoclassical growth model, and it is widely used in the development accounting literature (Klenow and Rodriguez-Clare, 1997;Hall and Jones, 1999; Hsieh and Klenow, 2010, et.al). On the steady state, capital-output ratio is a linear function of saving rate[4] , which implies that saving rate should be positively correlated with per capita output. Equation (1) also suggests that capital-output ratio must be positively correlated with per capital output. Figure 1 shows the relationship between capital-output ratio and real GDP per worker among 115 countries[5].

Figure1: Capital-output ratio and real GDP per worker: cross country evidence

The cross country evidence is consistent with neo-classic growth theory that capital-output ratio is positively related to real per capita output. As a comparison, figure 2 depicts the relationship between capital-output ratio and real GDP per worker across different provinces within China[6].

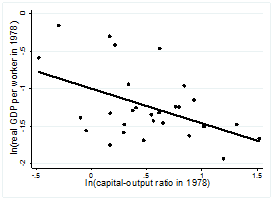

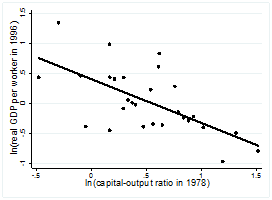

Figure2. Capital-output ratio and real GDP per worker: provincial evidence in China

The left panel shows that the capital-output ratio is negatively correlated to real GDP per worker in 1978, which contradicts with the prediction of neo-classic growth theory[7]. It may be argued that the positive effect of capital out-put ratio on output per worker does not reflect in 1978 data because China is a centrally planned economy before 1978. To address this concern, the right panel plots the relationship between capital-output ratio in 1978 and GDP per worker in 1996[8]. It is shown that, however, the negative correlation between capital-output ratio and GDP per worker is even stronger.

The puzzle of negative correlation between capital-output ratio and GDP per worker in China contradicts with neo-classic growth theory, and can hardly be explained by the more recent endogenous growth theory either. Among different endogenous growth models, the correlation between capital-output ratio and GDP per worker should also be non-negative[9].

A possible explanation to the puzzle is capital misallocation, which is pioneered by Hsieh and Klenow (2009), Restuccia and Rogerson (2008), Banerjee and Duflo (2005) et.al. Misallocation of capital will result in lower TFP and lower per capita output (Banerjee and Moll, 2010; Jones, 2011; Midrigan and Xu, 2010; Buera et.al, 2011, et.al). However, the effects of capital misallocation on capital-output ratio are ambiguous. Capital-output ratio will be lower if capital is misallocated to the labor intensive sector; while capital-output ratio will be higher if capital is misallocated to the capital intensive sector. In other words, the capital misallocation literature can hardly offer an explicit explanation to the puzzle without a deep understanding of the roots of misallocation.

We will argue throughout this paper that capital misallocation is a result of government development strategy. When the field of development economics started to take shape in the post-war period, the development economists encouraged governments in the LDCs to adopt interventional policies to accelerate capital accumulation and to pursue an "inward-looking" heavy-industry-oriented or an import-substitution strategy that directly aimed to close the industry/technology gap with the Developed Countries (DCs henceforth) (Chenery 1961, Warr 1994). These economists were strongly influenced by the Soviet Union's initial success in nation building, by the pessimism about the export of primary products formed during the Great Depression, by the lack of confidence in markets, and by the neoclassic growth theory (Rosenstein-Rodan 1943, Prebisch 1959). Since the 1950s, most LDCs, in both the socialist and capitalist camps, have adopted a variant of these strategies (Krueger 1992).

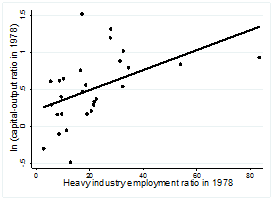

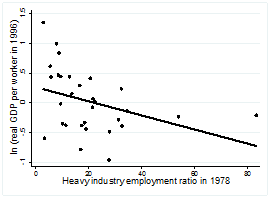

Heavy-industry-oriented development strategy implies that the government has to subsidy heavy industry sector because capital intensive sector is not consistent with the comparative advantage of most LDCs (Lin, 2003). Subsidies to heavy industry sector will lead to capital misallocation. Meanwhile, heavy-industry-oriented development strategy and capital misallocation will result in higher capital-output ratio and lower GDP per worker because the heavy industry is more capital intensive. The Chinese government also implements heavy-industry-oriented development strategy before 1978. Figure 3 depicts the relationship among government heavy industry employment ratio, capital-output ratio and GDP per worker in China[10].

Figure 3. Development strategy, capital-output ratio and GDP per worker

The left panel shows that a higher heavy industry employment ratio will result in a high capital-output ratio in 1978. Heavy industry oriented development strategy implies that the government will subsidy the capital intensive sector, which will lead to a higher capital-output ratio. Meanwhile, heavy industry oriented development strategy and misallocation will result in poor economic performance, which is reflected in the right panel. Figure 3 suggests that government development strategy is the possible driven force behind the negative correlation between capital-output ratio and GDP per worker. The following sections of this paper will study the relationship between government development strategy, misallocation and economic performance both theoretically and empirically, giving a consistent explanation to the puzzling negative correlation between capital-output ratio and GDP per worker.

III. Theoretic Framework

This section will construct a theoretic model to study the relationship between development strategy, resource misallocation and economic performance, which can reconcile the puzzling facts about the relationship between capital-output ratio and per capita income in China. The key intuition is that, if the government implements a heavy industry oriented development strategy, the capital-output ratio will be higher as heavy industry is more capital intensive; however, the per capita income will be lower as heavy industry, which is not compatible with the comparative advantage of the LDCs, is less efficient. In other words, heavy industry oriented development strategy will lead to a negative correlation between capital-output ratio and per capita income.

To investigate the effects of heavy industry oriented development strategy on economic development, we assume that there are two industries that can be chosen in the economy: labor-intensive industry and capital-intensive industry. And their production technologies are given by:

Where α<β, Fl(?) is the production function of